Elderberries – Sambucus spp.

- Author

- Name

- Sam Sycamore

- About

- Sam Sycamore is a writer, teacher, and forager who's been working with wild and cultivated plants for over a decade. He holds a B.S. in Biology from the University of Louisville. He previously hosted The Good Life Revival Podcast, where he explored topics related to permaculture, rewilding, climate change, and sustainability.

- Published on

- Last updated

Table of Contents

- What Are Elderberries?

- Are Elderberries Edible?

- Why Forage For Elderberries?

- Key Characteristics

- Etymology and Taxonomy

- Common Names

- Taxonomical Lineage

- Edible Wild Elderberry Species

- Where to Find Wild Elderberries

- When to Gather Elderberries

- How to Harvest and Prepare Elderberries

- How to Sustainably Work With Elderberries

- Wild Elderberry Lookalikes

- Water Hemlock

- Pokeweed

- Devil's Walking Stick

What Are Elderberries?

Elderberries are fast-growing deciduous suckering shrubs with gorgeous edible flowers and nutrient-rich berries, which are prized for their immune-boosting properties.

Are Elderberries Edible?

Elderberries and elder flowers are edible, BUT: the berries contain mildly toxic compounds and should not be consumed raw. Cooking elderberries neutralizes these compounds, making them safe to eat.

See the section below on how to harvest and prepare elderberries for further details.

Why Forage For Elderberries?

The elderberry is one of North America's most abundant fruits, but it tends to be overlooked in this era except by foragers who are interested in natural medicine.

The berries are traditionally made into syrups or extracts for treating cold and flu symptoms throughout the colder months of the year. They may also be processed for jams, jellies, or pies.

The flowers are edible as well and can be battered and fried or used for fermentation.

Key Characteristics

- Deciduous sun-loving shrub growing up to 20 feet tall with distinct wart-like lenticels protruding from the bark

- Pinnately compound leaves; leaflets with serrated margins

- Showy clusters of tiny white flowers with a fragrant aroma, followed by berries which may ripen to purple-black, blueberry-blue, or bright red, depending on the species

This close-up of some roadside elderberry flowers offers a clear illustration of their morphology.

Etymology and Taxonomy

Common Names

North American species names include black elderberries, blue elderberries, Canadian elderberries, and red elderberries.

The common name "elderberry" is believed to derive from the Anglo Saxon word æld, meaning fire, because its branches were often used to make bellows for blowing air into a fire.

The Latin name Sambucus comes from the Greek word sambyke, a sort of lyre/guitar-type instrument, referring to another use for elderberry wood in making musical instruments.

Taxonomical Lineage

Source: Wikipedia

Some taxonomies name S. nigra, S. canadensis, and S. cerulea as three distinct species; others treat the latter two North American natives as subspecies of the cosmopolitan S. nigra. The S. racemosa and S. mexicana may be subspecies of (or a synonym for) S. cerulea. Clearly the lines between Sambucus species are rather blurry.

Edible Wild Elderberry Species

When foraging for elderberries in North America, you may enounter dark purple-black berries (S. nigra), pale blue berries (S. cerulea), or bright red berries (S. racemosa) berries, depending on the species. The purple-black and pale blue are the edible ones—don't eat the red ones! If you do happen to accidentally nibble on one it should be unpalatably bitter, which should tell you to steer clear.

Black elderberries ripening in late summer on the edge of an urban park in Minnesota.

Where to Find Wild Elderberries

Black elderberries are common and abundant essentially everywhere east of the Rockies in North America. I've run into them all over the Midwest and Eastern US from Minnesota down to Georgia, and as far west as Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming.

Blue elderberries are found all up and down the Pacific coast and in some areas of the Southwest. I've spotted these as far east as Spokane, Washington.

Red elderberries have a more limited range in the Pacific Northwest and are also scattered across adjacent western and northern climes. I've seen them growing abundantly in the Tetons of Idaho and Wyoming.

Elderberries like woodland edges, roadsides, and hedge rows. They want slightly more fertile soil than some of the weedier edible wild plant species but will grow in a variety of conditions otherwise.

Because of their suckering habit, elderberries will sometimes form dense thickets where they are present, but they can be trained or trimmed to grow more like tame bushes.

The massive blooms of the elderberry are ubiquitous along the highways throughout the United States in the summer, but you may have never known who they were until now.

Elderberries are believed to be native to North America and Europe, though they have been intentionally cultivated and accidentally introduced well beyond their native ranges thanks to a long history of human interaction.

When to Gather Elderberries

Elderberries are among the earliest perennials to break dormancy in late winter.

The branches will be conspicuous all winter long, and once active in spring the distinctive foliage will be in full effect by April or May in most places at or near sea level.

Flowers will be blooming as early as May in the hotter parts of the continent and well into July, often still blooming anew while other clusters are dropping ripe berries. Expect birds to take care of all the berries by late summer if you don't get to them first.

A patch of elderberry bushes in bloom can be a spectacular sight in early summer.

How to Harvest and Prepare Elderberries

It's important to note before we go any further that the entire elderberry plant produces glycosidic compounds that break down and convert into hydrogen cyanide in your gut, which can make you very sick—up to and including death with a large enough dose—or at least very uncomfortable.

Though there are traditional indigenous medicines that make use of the bark and other vegetative material, it is not advisable for the non-herbalist forager to work with the plant in this way. Consider everything except the flowers and cooked, fully ripe berries to be toxic.

Why cooked? Elderberry seeds, which can be tough to separate from the flesh, contain those same glycosides as the rest of the plant, and so they can also make you sick when consumed raw. A couple berries to test in the field won't hurt you, but an ill-advised handful can. Applying heat neutralizes the glycosides and renders the berries safe to eat.

The following section is written with black and blue elderberries in mind. Though safe to consume after heating, all elderberries may still cause mild gastric distress in some individuals, so ease your way in if you're new to this food.

Red elderberries have traditional medicinal uses but are not commonly gathered as food for humans today. There is evidence to indicate that indigenous peoples once consumed them widely but usually cooked them and were careful to remove the seeds first. Still, they are described in the literature as unpleasant at best even when properly prepared, so I wouldn't advise it.

Keep in mind when harvesting from a wild patch that although elderberries are prolific, they are also an important food source for a wide range of non-human critters, so don't be too greedy. The plants don't care how much you take, but you could be robbing pollinators, birds, and various mammals of many meals.

Elderflowers are produced in dense globe-like clusters referred to as cymose corymbs (or just cymes), which at first glance look very similar to the compound umbels of the Apiaceae (carrot) family, but are scientifically differentiated by their branching pattern which you might describe as "irregular" or "asymmetrical."

Whether you're gathering flowers or berries, it is much simpler to harvest whole cymes than to pick individual fruits. To do this, simply come prepared with scissors or pruners and a basket that's much larger than what you think you'll need, to accommodate all of the stems you'll be carrying along for the ride.

Elderflowers will quickly wilt and their lovely fragrant aroma will fade within a few hours of harvesting, so plan to use them immediately.

For berries, you will need to remove the stems and sort through the fruits individually to pick out those that are unripe, rotten, or otherwise unusable. Freezing the whole cymes beforehand will make it easier to knock the berries off the stems.

If you can afford to take your sweet time out in the field, you might opt to harvest individual berries by hand rather than sorting at home later. For the purposes of meditation and nature connection, you might prefer this method; but if time is your biggest limiting factor, gather whole cymes and sort out stems later.

Once you've gathered and sorted your berries, toss them in a pot with some water and let them gently simmer near boiling for a moment. Strain off the water and then either process further or else store in an airtight container in the freezer until you're ready to use them.

When baking or making preserves, you will want to add something acidic like lemon juice or a tart companion berry, such as any brambleberry that may be ripe when your elderberries show up.

Elderberry wine is well known to many, if only by name, perhaps because it takes at least three pounds of berries to produce a gallon of wine. As any seasoned elderberry forager will tell you, three pounds is a pretty serious accomplishment. Maybe that's worth celebrating in kind.

How to Sustainably Work With Elderberries

Elderberries are among the simplest and easiest perennial shrubs to propagate. This is due in part to the presence of lenticels on the surface of the stems. These unique structures can sprout roots when they come in contact with soil or water, and they will do so approximately 99.9%* of the time, according to my calculations. _(*Not a scientific measurement.)_

The lenticels on this black elderberry are very pronounced.

The process for propagating elderberries is essentially the same as with brambleberries, only simpler: you can layer or bend a stem over to the ground and allow it to root at its nodes, then prune it from the parent plant once established; or you can take cuttings to root at home.

The main difference from brambles is that elderberry cuttings will readily grow new roots when you stick them in a couple inches of water, and since they can sprout roots from the lenticels, you don't even necessarily need to include any nodes on the part of the stem that will be underground (though it's still a good idea to plan for at least or two underground nodes, which will usually send up new suckers and develop their own roots).

And with elderberries there is no primocane/floricane distinction to be made, as with the brambles. Young spring growth will give you the best chances, but pretty much every cutting I've ever taken from an elderberry has at least attempted to grow, even if it didn't take in the end. Six inches per cutting is a good rule of thumb.

Elderberry cuttings freshly harvested from a patch in early spring.

Some growers will soak their fresh cuttings for a period of time, perhaps a day or two, and then transfer to a soil-free medium (perlite/vermiculite + peat moss/coco coir + compost). I just leave my cuttings in water indefinitely, and they will usually sprout roots along with new green growth at the nodes within a few weeks. In fact it's very rare in my experience that a cutting does not sprout new growth. Once I see some decent root growth, I will transfer my cuttings to pots so they can get established before transplanting in the ground.

This black elderberry cutting is ready to planted in soil.

Just like with the brambles (and any other perennials), your young elderberry cuttings will want "Goldilocks" conditions: not too hot, not too cold, not too dry, not too wet... Thankfully, they are among the most forgiving species you will ever work with in this way. Warm and humid is preferred over cold and dry. Before they're established they will be somewhat sensitive to too much sunlight, so go easy on them.

Because elderberries produce many suckering shoots from their root systems, you can sometimes dig up suckers you find growing adjacent to an established plant, which will be connected to the main plant's roots but will probably have their own hairy young roots as well. In this case, snip them off from the parent plant and grow them out in a pot from there. But even if you just cut the shoots at soil level, no roots attached, you'll still have a high success rate growing new clones from them.

Wild Elderberry Lookalikes

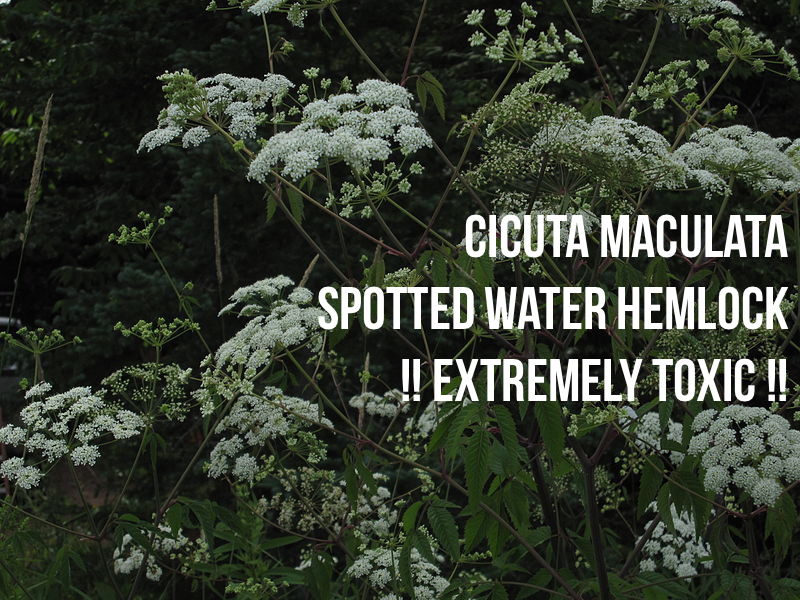

Water Hemlock

Spotted water hemlock is very toxic. Be mindful of the differences when harvesting elderflowers.

Many folks worry about mistaking the flowers of the water hemlocks (Cicuta spp.)—North America's deadliest plants by a long shot—with those of the elderberry, but I believe it's pretty difficult to make this mistake if you are familiar with any other traits of these plants.

The flower clusters looks quite different to my eyes, as water hemlock clearly shows off its Apiaceae compound umbels, while elderberries do not. Also, water hemlock doesn't produce any kind of fruit that resembles an elderberry, so if you can't get a positive ID on the flowers, just wait and see what happens when they mature.

Pokeweed

Other would-be elder foragers worry about mistaking pokeberries for elderberries, but this is also pretty tough to do if you know that pokeweed, Phytolacca americana, is an herbaceous annual that produces its fruits in elongated raceme clusters that hang down from the plant.

Devil's Walking Stick

Yet another similar plant to be aware of is Aralia spinosa, commonly known as Devil's walking stick or sometimes Hercules' club. This woody perennial shrub has similar foliage and produces clusters of purple-black berries around the same time as Sambucus spp. The verdict is out on the edibility of A. spinosa berries, but I can tell you from firsthand sampling that they taste very unpleasant and would be tough to mistake for elderberries when tested by the tongue. But the easiest way, by far, to differentiate between these species is to look out for the sharp spines that cover the stems and branches of the Devil's walking stick and earn it such a sinister common name.

Devil's walking stick, Aralia spinosa. Photo: Richard Chambers via Wikimedia Commons.

Foraging North America

Did you find this article helpful?

This is an excerpt from Foraging North America: The Botany, Taxonomy and Ecology of Edible Wild Plants.

Foraging North America is a 12-week crash course designed to arm you with a functional working knowledge of botany and taxonomy that you can take with you out onto the land to fast-track the ID process and boost your confidence when gathering wild foods for the first (or five-hundredth!) time.

You'll get a practical education in ecological literacy by applying the ethos of conservation through use—the (surprisingly) radical notion that humans can, in fact, have a positive impact on the environments that we move through.

Food is everywhere—you just need to know what to look for!